chapter four

4 Data and logic

This chapter covers

- What a simple data-oriented architecture looks like.

- Where to store the balance data - the data that doesn’t change during gameplay.

- Where to store the game data - the data that changes during gameplay.

- How to implement our game logic functions.

In the previous chapters, we learned how to write high-performance code using data-oriented design. Now we’ll use what we learned in chapters 1-3 to architect a simple version of our survivor game. In this chapter, we’ll cover the parts that are engine agnostic: the game data and the static logic functions that transform it. In Chapter 5, we’ll cover the board, which takes in input and draws our sprites to the screen, and the game loop, which drives our board and controls our menus.

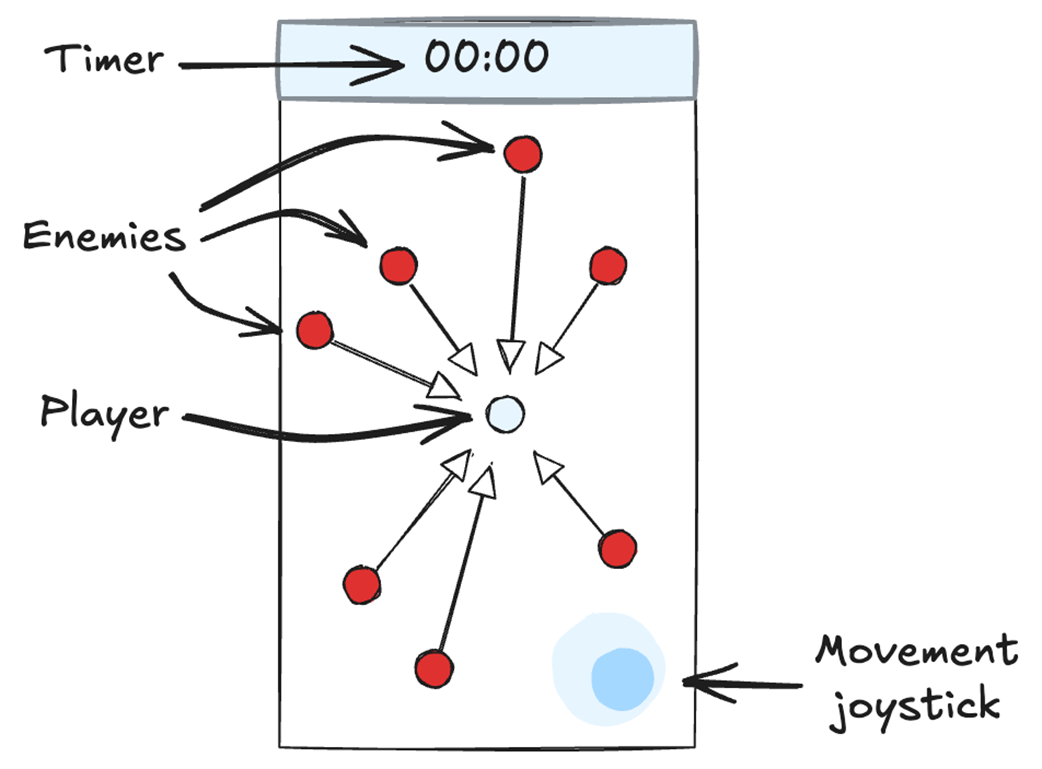

To help show what a DOD architecture looks like, we will create a basic version of our survivor/bullet-heaven game, as shown in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Screenshot from our basic survivor game. The player is the black dot in the middle. The enemies are the red dots. The user can move the player around the screen while the enemies all move towards the player. If the player touches an enemy, the game is over.

The gameplay is simple: