2 Concurrency

This chapter covers fundamental programming concepts: - Concurrency: Concepts and primitives to reason about concurrent work safely.

2.1 Concurrency vs. Parallelism

2.1.1 Differences

It’s fairly common for developers to mix up the concepts of concurrency and parallelism, but they are actually quite distinct. Let’s approach these two concepts using a coffee shop analogy.

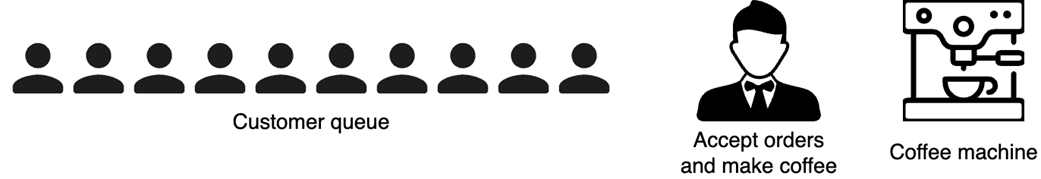

Imagine a coffee shop with one waiter who takes orders and makes coffee using a single machine. Customers wait in line, place their orders, and then wait for their coffee:

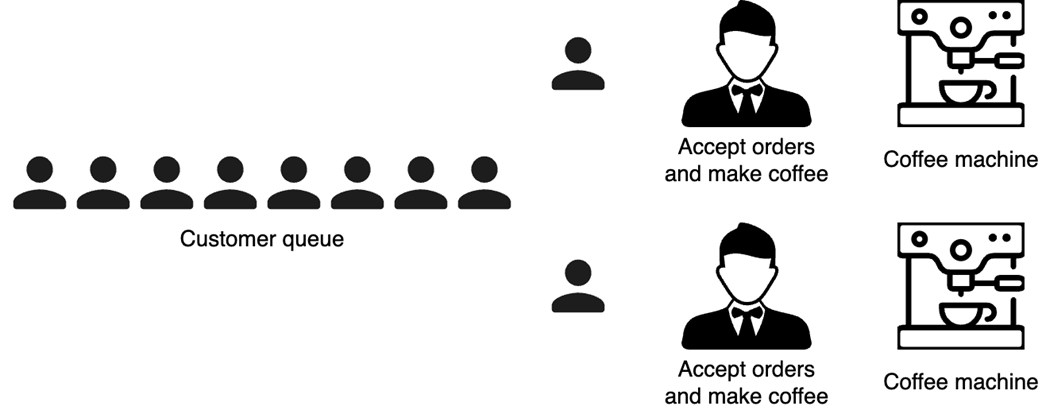

If the waiter struggles to keep up with the number of customers, the coffee shop owner may decide to speed up the overall process by engaging a second waiter and buying a second coffee machine. Now, two waiters can serve customers at the same time:

In this setup, the two waiters work independently. Each has its own coffee machine, allowing the shop to serve customers twice as fast. This is parallelism—executing multiple tasks simultaneously by adding more resources (waiters and machines).

If we want to scale further, we can keep adding more waiters and machines, but this approach has its limits. For example, buying multiple coffee machines can become overly expensive.