This first chapter is as easy as Rust gets and has a bit of everything to get started. You’ll notice that even in Rust’s easiest data types, there’s a strong focus on the bits and bytes that make up a computer’s system. That means there’s quite a bit of choice, even in simple types like integers. You’ll also start to get a feel for how strict Rust is. If the compiler isn’t satisfied, your program won’t run! That’s a good thing—it does a lot of the thinking for you.

highlight, annotate, and bookmark

You can automatically highlight by performing the text selection while keeping the alt/ key pressed.

The Rust language was only released in 2015 and, as of 2024, isn’t even a decade old. It’s quite new but already very popular, appearing just about everywhere you can think of—Windows, Android, the Linux kernel, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Discord, Cloudflare, you name it. It is incredible how popular Rust has become after less than a decade. Rust earned its popularity by giving you almost everything you could want in a language: the speed and control of languages like C or C++, the memory safety of other newer languages like Python, a rich type system that lets you avoid bugs, and a friendly compiler that helps you when you go wrong. It does this with some new ideas that are sometimes different from other languages. That means there are some new things to learn, and you can’t just “figure it out as you go along.” Rust is a language you have to think about for a while to understand.

So Rust is a language that is famously difficult to learn. But I don’t agree that Rust is difficult. Programming itself is difficult. Rust simply shows you these difficulties when you are writing your code, not after you start running it. That’s where this saying comes from: “In Rust, you get the hangover first.” In many other languages, the party starts first: your code compiles and looks great! Then you run your code, and there’s a lot to debug. That’s when you get the hangover.

The hangover in Rust is because you have to satisfy the compiler that you are writing correct code. If your code doesn’t satisfy the compiler, it won’t run. You can’t mix types together, you have to handle possible errors, you have to decide what to do when a value might be missing, etc. But as you do that, the compiler gives you hints and suggestions to fix your code so that it will run. It’s tough work, but the compiler tries to guide you along the way. And when your code finally compiles, it works great.

In fact, because of that, Rust was the first language that I was properly able to learn. I loved how friendly the compiler was when my code didn’t compile. The compiler felt like a teacher or a co-programmer. It was also interesting how the errors taught me about how computers use memory. Rust wasn’t just a language that let me build software; it was a language that taught me details about the inner workings of computers that I never knew before. The more I used it, the more I wanted to know, and that’s why I was able to learn Rust as my first language. I hope this book will help others learn it, too, even if Rust is their first programming language.

Rust is a fairly easy language. Seriously! Well, sort of. Yes, it’s complex and takes a lot of work to learn. Yes, most people who learn Rust have frustrating days (sometimes unbearingly frustrating days) where they just want their code to compile and don’t understand what to do.

But this period does not last forever. After the period is over, Rust becomes easier because it starts doing a lot of the thinking for you. Rust is the type of language that allows junior developers to start working on an existing code base with confidence because, for the most part, it simply won’t compile if there’s a problem with your code. Sometimes you hear horror stories about junior developers who join a company and simply aren’t able to contribute yet. They see a code base and ask if they can make a change, but the senior developers say not to touch it “because it’s working and who knows what will happen if you make a change.” Rust isn’t like that.

That makes contributing and refactoring code, well, easy. If you watch Rust live streams on YouTube or Twitch, you’ll see this happen a lot. The streamer will make a bunch of changes to some existing code and then say, “Okay, let’s see what breaks.” The compiler then gives a few dozen messages showing what parts don’t work anymore, and then the streamer hunts them down one by one and makes the necessary changes until it compiles again—usually in just a few minutes. Not a lot of languages can do that.

A great analogy for Rust is that of a critical but helpful spouse. Imagine you have a job interview and are getting ready to head out the door and ask your spouse how you look. Let’s see how two types of spouses treat you: the lenient language spouse and the strict Rust spouse.

The lenient language spouse sees you going out the door and calls out: “You look great, honey! Hope the interview goes well!” And off you go! You’re feeling good. But maybe you don’t look great and don’t realize it. Maybe you forgot to prepare a number of important things for the interview. If you’re an expert in interviews, you’ll do fine, but if not, you might be in trouble.

The Rust spouse isn’t so lenient and won’t even let you out the door: “You’re going out wearing that? It’s too hot today; you’ll be sweating by the time you get in. Put on that suit with the lighter fabric.” You change your suit.

The Rust spouse looks at you again and says, “The suit you just changed into doesn’t match your socks. You need to change to grey socks.” You grumble and go change your socks.

The Rust spouse still isn’t satisfied: “It’s windy today, and it’s at least a quarter-mile walk from the parking lot to the company. Your hair is going to be messy by the time you get there. Put some gel in.” You go back to the bathroom and put some gel in your hair.

The Rust spouse says, “You still can’t go. The parking lot you’ll be using was built a long time ago and doesn’t take credit cards. You need $2.50 in change for the machine. Find some change.” Sigh. You go and look around for some loose change. Finally, you gather $2.50.

This repeats and repeats another 10 times. You’re starting to get annoyed, but you know your spouse is right. You make yet another change. Is it the last one?

Eventually, your Rust spouse looks you up and down, thinks a bit, and says: “Fine. Off you go.” Yes! Finally! That was a lot of work.

You head out the door, still a bit frustrated by all the changes you had to make. But you walk by a window and see your reflection. You look great! It’s windy today, but your hair isn’t being blown around. You pull into the parking lot and put in the $2.50—just the right amount of change.

You look around and see someone else arriving for the interview in a suit that’s too heavy and is already sweating. His socks don’t match the suit. He only has a credit card and is trying to find a store nearby to get some change. He starts walking to the store, his hair in a mess as the wind blows it every which way. But not you—your spouse did half of the work for you before you even started. So, in that sense, Rust is a really easy language.

If you think about it, programs live at run time, but programmers can only see up to compile time—the time before a program starts. If your code compiles, you run it and hope for the best. You can’t control the program anymore once it starts.

If your language isn’t strict at compile time, most of the possible errors will happen at run time instead, and you will have to debug them. Rust is as strict as possible at compile time, where you, the programmer, live. So Rust teaches you as much as it can about your program before you even run it.

Okay, what does this actually look like in practice? Let’s take a look at a real example. We’ll go to the Rust Playground (https://play.rust-lang.org/), write some incorrect Rust code, and see what happens. We’ll try to make a String and then push a single character to it and print it out:

fn main() {

let my_name: String = "Dave";

my_name.push("!");

println!("{}" my_name);

}

This is pretty good for a first try at Rust, but it’s not correct yet. What does the Rust compiler have to say about that? Quite a bit, in fact. It gives you three suggestions:

error: expected `,`, found `my_name` | 4 | println!("{}" my_name); | ^^^^^^^ expected `,` error[E0308]: mismatched types --> src/main.rs:2:27 | 2 | let my_name: String = "Dave"; | ------ ^^^^^^- help: try using a conversion method: `.to_string()` | | | | | expected struct `String`, found `&str` | expected due to this error[E0308]: mismatched types --> src/main.rs:3:18 | 3 | my_name.push("!"); | ---- ^^^ expected `char`, found `&str` | | | arguments to this function are incorrect | help: if you meant to write a `char` literal, use single quotes | 3 | my_name.push('!'); | ~~~

fn main() {

let my_name: String = "Dave".to_string();

my_name.push('!');

println!("{}", my_name);

}

fn main() {

let mut my_name: String = "Dave".to_string();

my_name.push('!');

println!("{}", my_name);

}

And it works! That’s the combination of strictness and helpfulness that the Rust compiler is famous for. You will understand all of this code within just a few chapters, so don’t worry about it too much now.

One final note before we get into chapter 1: the Rust compiler is smart enough to know if you wrote some code you never used. In that case, it will give you a warning so that you will remember that you wrote something you haven’t used yet. In this book, many examples have code to teach a concept and never gets used, so don’t worry about those warnings.

fn main() {

let my_number = 9;

}

This is a hint from the compiler to let you know that you created a variable but didn’t do anything with it. It doesn’t mean there is a problem with your code, so don’t worry.

discuss

Comments are made for programmers to read, not the computer. It’s good to write comments to help other people understand your code. It’s also good to help you understand your code later (many people write good code but then forget why they wrote it). To write comments in Rust, you usually use // like in the following example:

The let some_number = 100; part of the code, by the way, is how you make variables in Rust. A variable is basically a piece of data with a name chosen by us—hopefully a good name—so that later on we will remember what sort of data the variable is holding. Here, we are telling Rust to take this piece of data (the number 100) and give it the name some_number so that we can use some_number later to access the number 100 it holds. The variable name could differ depending on the context: we might write let perfect_score = 100;, for example, if the number 100 represented a perfect score on a test.

There is another kind of comment that you write with /* to start and */ to end. A comment wrapped in /* and */ is useful to write in the middle of your code:

fn main()

let some_number/*: i16*/ = 100;

}

To the compiler, let some_number/*: i16*/ = 100; looks like let some_number = 100;. The /* */ form is also useful for very long comments of more than one line. In the following example, you can see that you need to write // for every line. But if you type /*, the comment won’t stop until you finish it with */:

fn main() {

let some_number = 100; // Let me tell you

// a little about this number.

// It's 100, which is my favorite number.

// It's called some_number but actually I think that...

let some_number = 100; /* Let me tell you

a little about this number.

It's 100, which is my favorite number.

It's called some_number but actually I think that... */

}

If you see /// (three slashes), that’s a “doc comment” (documentation comment). A doc comment can be automatically made into documentation for your code. Documentation is used to explain how code works, usually for other people to read, but it can be good for you, too, so you won’t forget. All the information on documentation pages like http://doc.rust-lang.org/std/index.html is made with doc comments.

So // means comments for inside the code, while /// is for more official information to be shared beyond the code itself. Regular // comments can be very informal, like this:

// todo: delete this after Fred updates the client.

/// Converts a string slice in a given base to an integer. Leading and trailing whitespace represent an error.

(We’ll look at doc comments later in the book. But if you have Rust installed already and are curious, try writing some comments and then typing cargo doc --open to see what happens.)

So comments are pretty easy because Rust doesn’t notice them at all. Let’s move on to another pretty easy subject: Rust’s simplest types.

settings

Rust has many types that let you work with numbers, characters, and so on. Some are simple, and others are more complicated; you can even create your own.

The simplest types in Rust are called primitive types (primitive = very basic). We will start with two of them: integers and characters. Rust has a lot of integer types, but they all have one thing in common: they are whole numbers with no decimal point. There are two types of integers: signed integers and unsigned integers.

So what does signed mean exactly? It’s simple: signed means + (plus sign) and − (minus sign). So, signed integers can be positive or negative (e.g., +8, −8) or zero. But unsigned integers (e.g., 8) can only be nonnegative because they do not have a sign. The signed integer types are i8, i16, i32, i64, i128, and isize. The unsigned integer types are u8, u16, u32, u64, u128, and usize.

The number after the i or the u means the number of bits for the number, so numbers with more bits can be larger: 8 bits = 1 byte, so i8 is 1 byte, i64 is 8 bytes, and so on. Number types with more bits can hold much larger numbers:

- u8 can hold a number as large 255.

- u16 can hold a number as large as 65,535.

- u128 can hold a number as large as 340,282,366,920,938,463,463,374,607,431,768,211,455.

A quick explanation of how integers work: computers use binary numbers, while people use decimals. Binary means 2, and decimal means 10, so you have two possible digits for binary (0 or 1) and 10 possible digits (0 to 9) for decimal.

With decimals, you move up by 10 at a time: 100 is 10 times more than 10, 1,000 is 10 times more than 100, and so on. But computers increase numbers in binary by 2, not 10. Here’s what this doubling looks like over the 8 bits of a u8.

You can see that there are eight spaces for numbers, which are the bits. Each bit is for a number two times larger than the last one. A bit can be a 0 or a 1—nothing else. When a bit shows up as 0, the number isn’t counted; if it shows up as 1, it is counted.

If you have a decimal number with eight digits, the highest number you can get is 99,999,999. Reading from right to left, you can think of this number as being made of a 9, a 90, a 900, a 9,000, a 90,000, a 900,000, a 9,000,000, and a 90,000,000. Put them all together, and you get 99,999,999. Now, if you do the same for binary, the highest number you can get over eight digits is 11111111. And if you count up these numbers, you get 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 + 64 + 128 = 255. That’s why 255 is the largest size for a u8. And if you move to a u16, you have eight more spaces, each one two times larger than the last. So a u16 is all those plus 256, then 512, and so on. Consequently, the highest number for a u16 is 65,535 (a lot higher), even though it’s only two times the size (16 bits, or 2 bytes).

You can also think of it as this: a human cashier at the grocery who asks you to pay $226 is asking for

But what a “machine cashier” asks you for is 11100010, which is (remember, going from right to left):

Putting all that together, you get: 2 + 32 + 64 + 128 = 226. And that’s why the u8 for 226 looks like this.

Signed integers have a maximum value that is only half that of an unsigned type of the same number of bits because they also have to represent negative numbers. So a u8 goes from 0 to 255 while an i8 goes from −128 to 127.

So what about isize and usize, and why are there no numbers in their name? These two types have a number of bits depending on your type of computer. (The number of bits on your computer is called the architecture of your computer.) So isize and usize on a 32-bit computer is like i32 and u32, and isize and usize on a 64-bit computer is like i64 and u64.

There are many reasons why Rust has a lot of integer sizes. One reason is com-puter performance: a smaller number of bytes can be faster to process. For example, the number –10 as an i8 is 11110110, but as an i64, it is 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111110110. The lar-ger type has a greater maximum number but still uses the same number of bits, even if the number is a small one. But there are quite a few other reasons for having a lot of integer sizes. One is related to the char type, which is related to one of Rust’s integer types.

Characters in Rust are called char. Every char has a number: the letter A is number 65, while the character 友 is number 21451. The list of numbers is called Unicode. Unicode uses smaller numbers for basic characters like A through Z, digits 0 through 9, or space. New languages get added to Unicode all the time, and some languages have thousands of characters, which is why 友 is such a high number.

fn main() {

let first_letter = 'A';

let space = ' '; #1

let other_language_char = 'Ꮔ'; #2

let cat_face = '😺'; #3

}

So you won’t be able to fit all chars into something as small as a u8, for example. But the characters used most (called ASCII) are represented by numbers less than 256, and they can fit into a u8. Remember, a u8 is 0 plus all the numbers up to 255, for 256 characters in total. This means that Rust can safely “cast” a u8 into a char, using as. (“Cast a u8 as a char” means “turn a u8 into a char.”)

Casting with as is useful because Rust is very strict. It always needs to know the type and won’t let you use two different types together, even if they are both integers. For example, this will not work:

fn main() { #1

let my_number = 100; #2

println!("{}", my_number as char);

}

error[E0604]: only u8 can be cast as char, not i32

--> src\main.rs:3:20

|

3 | println!("{}", my_number as char);

| ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

By the way, you’ll see println!, {}, and {:?} in this chapter a bit. Typing println! will print and then add a new line, while {} and {:?} describe what type of printing. println! is known as a macro. A macro is a function that writes code for you; all macros have a ! after them. You don’t need to worry about remembering to add the ! because the compiler will notice if you don’t:

fn main() {

let my_number = 100;

println("{}", my_number);

}

error[E0423]: expected function, found macro `println`

--> src/main.rs:3:5

|

3 | println("{}", my_number);

| ^^^^^^^ not a function

|

help: use `!` to invoke the macro

|

3 | println!("{}", my_number);

|

Now, back to our my_number as char problem. Fortunately, we can easily fix this with as. We can’t cast i32 as a char, but we can cast an i32 as a u8. Then we can do the same from u8 to char. So, in one line, we use as to make my_number a u8 and again to make it a char. Now it will compile:

fn main() {

let my_number = 100;

println!("{}", my_number as u8 as char);

}

So casting can be convenient. But be careful: when you cast a large number into a smaller type, some unexpected things can happen. For example, a u8 can go up to 255. What happens if you cast the number 256 into a u8?

fn main() {

let my_number = 256;

println!("{}", my_number as u8);

}

fn main() {

let my_number = 600;

println!("{}", my_number as u8);

}

Now it returns an 88. You can probably see what it’s doing now: every time it passes the largest possible number, it starts at 0 again. So when you cast a 600 to a u8, it passes the largest possible u8 two times, and then there are 88 left. You can think of it mathematically as 600 − 256 − 256 = 88. So be a little careful when casting into a smaller type! When casting, make sure the old number isn’t larger than the new type’s largest possible number.

In fact, casting is somewhat rare in Rust because there is usually no need for it. For example, you don’t need to use a cast to get a u8. You can just tell Rust that my_ number is a u8. Here’s how you do it:

fn main() {

let my_number: u8 = 100; #1

println!("{}", my_number as char);

}

So those are two reasons for all the different number types in Rust. Here is another reason: usize is the size Rust uses for indexing. (Indexing means “which item is first,” “which item is second,” etc.) A usize is the best size for indexing because

- An index can’t be negative, so it needs to be an unsigned integer with a u.

- It should have a lot of space because index numbers can get quite large (but it can’t be a u64 because 32-bit computers can’t use a u64).

Let’s learn some more about char. You saw that a char is always one character and uses ' ' (single quotes) instead of " " (double quotes).

- Basic letters and symbols usually need 1 byte, (e.g., a b 1 2 + - = $ @).

- Other letters like German umlauts or accents need 2 bytes (e.g., ä ö ü ß è à ñ).

- Korean, Japanese, or Chinese characters need 3 or 4 bytes (e.g., 国 안 녕).

So, to be sure that a char can be any of these, it needs to be 4 bytes. With 2 bytes (a u16), the largest number you can make is 65,535, which is well below the number of letters in all the languages in the world (Chinese characters alone are more than this!). But a u32 (4 bytes) offers more than enough space, allowing for up to 4,294,967,295 letters, which is why a char is a u32 on the inside.

But always using 4 bytes is just for the char type. Strings are different and don’t always use 4 bytes per single character. When a character is part of a string (not the char type), the string is encoded to use the least amount of memory needed for each character.

We can use a method called .len() to see this for ourselves. Try copying and pasting this and clicking Run:

fn main() {

println!("Size of a char: {}", std::mem::size_of::<char>());

println!("Size of a: {}", "a".len());

println!("Size of ß: {}", "ß".len());

println!("Size of 国: {}", "国".len());

println!("Size of 𓅱: {}", "𓅱".len());

}

(By the way, std::mem means the part of the standard library called mem where this size_of() function is. The :: symbol is used sort of like a path to an address. It’s sort of like writing USA::California::LosAngeles. We will learn about this later.)

Size of a char: 4 Size of a: 1 Size of ß: 2 Size of 国: 3 Size of 𓅱: 4

You can see that a is 1 byte, the German ß is 2, the Japanese 国 (meaning country) is 3, and the ancient Egyptian 𓅱 (a quail chick) is 4 bytes.

Let’s try printing the length of two strings, one with six letters and the other with three letters. Interestingly, the second one is larger:

fn main() {

let str1 = "Hello!";

println!("str1 is {} bytes.", str1.len());

let str2 = "안녕!"; #1

println!("str2 is {} bytes.", str2.len());

}

str1 is 6 bytes. str2 is 7 bytes.

str1 is six characters in length and 6 bytes, but str2 is three characters in length and 7 bytes. So be careful! The .len() method returns the number of bytes, not the number of letters or characters.

By the way, the size of a byte is one u8: it’s a number that goes from 0 to 255. We can use a method called .as_bytes() to see what these strings look like as bytes:

fn main() {

println!("{:?}", "a".as_bytes());

println!("{:?}", "ß".as_bytes());

println!("{:?}", "国".as_bytes());

println!("{:?}", "𓅱".as_bytes());

}

You can see that each one is different and that to show them all in a single type, it needs 4 bytes. And that’s why the char type is 4 bytes long:

[97] [195, 159] [229, 155, 189] [240, 147, 133, 177]

Now, if .len() gives the size in bytes, what about the size in characters? You can find this out by using two methods together. We will learn about these methods in more detail later in the book (especially chapter 8), but for now, you can just remember that .chars().count() will give you the number of characters or letters, not bytes. Calling .chars() first turns a string into a collection of characters, and then .count() counts how many of them there are.

fn main() {

let str1 = "Hello!";

println!("str1 is {} bytes and also {} characters.", str1.len(), str1.chars().count());

let str2 = "안녕!";

println!("str2 is {} bytes but only {} characters.", str2.len(), str2.chars().count());

}

str1 is 6 bytes and also 6 characters. str2 is 7 bytes but only 3 characters.

You might have noticed already that you don’t usually need to tell Rust the type of variable you’re making. The Rust compiler is happy with let letter = 'ß' and doesn’t make you type let letter: char = 'ß' to declare a char. Let’s learn why!

highlight, annotate, and bookmark

You can automatically highlight by performing the text selection while keeping the alt/ key pressed.

The term type inference means that Rust can usually decide what type a variable is even if you don’t tell it. The term comes from the verb infer, which means to make an educated guess.

The compiler is smart enough that it can usually “infer” the types that you are using. In other words, it always needs to know the type of variables you are using, but most of the time, you don’t need to tell it. For example, if you type let my_number = 8, the variable my_number will be an i32. That is because the compiler chooses i32 for integers unless you tell it to choose a different integer type. But if you say let my_number: u8 = 8, it will make my_number a u8 because you told it to make a u8 instead of an i32.

- You are doing something very complex, and the compiler can’t determine the type you want.

- You simply want a different type (e.g., you want an i128, not an i32).

fn main() {

let small_number: u8 = 10;

}

For numbers, you can add the type after the number. You don’t need a space—just type it right after the number:

fn main() {

let small_number = 10u8; #1

}

fn main() {

let small_number = 10_u8;

let big_number = 100_000_000_i32;

}

The _ is only to make numbers easy for humans to read and does not affect the number. It is completely ignored by the compiler. In fact, it doesn’t matter how many _ you use:

fn main() {

let number = 0________u8;

let number2 = 1___6______2____4______i32;

println!("{}, {}", number, number2);

}

Interestingly, if you add a decimal point to a number, it won’t be an integer (a whole number) anymore. Rust will instead make a float, which is an entirely different type of number. Let’s learn how floats work now.

discuss

Floats are numbers with decimal points. 5.5 is a float, and 6 is an integer. 5.0 is also a float, and even 5. is a float. The variable my_float in the following code won’t be an i32 because of the decimal point that follows it:

fn main() {

let my_float = 5.;

}

But these types are not officially called floats; they are called f32 and f64. As you can imagine, the numbers in their type names show the number of bits needed to make them: 32 and 64 (4 bytes and 8 bytes). In the same way that Rust chooses an i32 by default, it will also choose f64 unless you tell it to make an f32.

Of course, Rust is strict, so only floats of the same type can be used together. You can’t add an f32 to an f64. We can generate an error by telling Rust to make an f64 and an f32 and then trying to add them together:

fn main() {

let my_float: f64 = 5.0;

let my_other_float: f32 = 8.5;

let third_float = my_float + my_other_float;

}

The compiler writes “expected (type), found (type)” when you use the wrong type. It reads your code like this:

- let my_float: f64 = 5.0;—Here we specifically tell the compiler that my_ float must be an f64.

- let my_other_float: f32 = 8.5;—And here we say that my_other_float must be an f32. The compiler does what we tell it to do.

- let third_float = my_float +—At this point, the variable that follows my_ float has to be an f64. The compiler will expect an f64 to follow.

- my_other_float;—But it’s an f32, so it can’t add them together.

So when you see “expected (type), found (type)”, you must find why the compiler expected a different type.

fn main() {

let my_float: f64 = 5.0;

let my_other_float: f32 = 8.5;

let third_float = my_float + my_other_float as f64; #1

}

But there is an even simpler method: remove the type declarations (to declare a type just means to tell Rust to use a type) and let Rust do the work for us. Rust will choose types that can be added together. In the following code, Rust will make each float an f64:

fn main() {

let my_float = 5.0;

let my_other_float = 8.5;

let third_float = my_float + my_other_float;

}

The Rust compiler is pretty smart and will not make an f64 if we declare an f32 and try to add it to another float:

fn main() {

let my_float: f32 = 5.0;

let my_other_float = 8.5; #1

let third_float = my_float + my_other_float; #2

}

You’re probably wondering when we’re going to look at “Hello, World!,” which is usually the first example you see when learning a programming language. That time is now!

settings

Take our tour and find out more about liveBook's features:

- Search - full text search of all our books

- Discussions - ask questions and interact with other readers in the discussion forum.

- Highlight, annotate, or bookmark.

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world!");

}

- fn means function.

- main() is the function that starts the program.

- () means that we didn’t pass the function any arguments (an argument is an input to a function). So, that means the function is starting without any variables that it can use.

After that comes {}, which is called a code block. Code blocks are spaces where code lives. If you start a variable inside a code block, it will live until the end of the block. This is its lifetime. Let’s look at the example with floats from before, but we’ll put one of them inside its own code block. Now, it won’t live until the end of the program:

fn main() {

let my_float = 5.0; #1

{

let my_other_float = 8.5; #2

} #3

// let third_float = my_float + my_other_float; #4

} #5

A {} doesn’t always mean a code block in Rust, though. The following code shows {} being used to change the output in main to add a number 8 after Hello, world:

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world number {}!", 8);

}

The {} in println! means “put the variable inside here.” In other words, the {} is used to capture the variable. This prints Hello, world number 8!.

fn main() {

println!("Hello, worlds number {} and {}!", 8, 9);

}

Did you notice that a ; comes at the end of the line? This is a semicolon, and it has a particular meaning in Rust.

We can see what the semicolon is used for by creating a simple function. We’ll call it give_number and put it above main(). (Usually, you put main() on the bottom, but it makes no difference). Then we’ll call this function inside main by typing give_ number():

fn give_number() -> i32 {

8

}

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world number {}!", give_number());

}

This also prints Hello, world number 8!. When Rust looks at give_number(), it sees that you are calling a function. This function

- Does not take anything because there’s nothing inside ().

- Returns an i32. The -> (called a skinny arrow) shows what the function returns.

Inside the function is just 8. Because there is no semicolon at the end of the line, this 8 (an i32) is the value the function give_number() returns. If it had a semicolon at the end, it would not return anything (it would return a (), which is called the unit type and means “nothing”).

So here’s the important part: Rust will not compile this program if the function’s body ends with a ; because the return type is i32, and with ;, the function returns (), not i32. Let’s try adding ; to see the error. Now our code looks like this:

fn give_number() -> i32 {

8;

}

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world number {}", give_number());

}

This means “you told me that give_number() returns an i32, but you added a ; so it doesn’t return anything.” So, the compiler suggests removing the semicolon.

You can also write return 8; to return a value, but in Rust, it is normal to remove the return. The last line of the function is what the function returns, and you don’t need to type return to make the return happen. Of course, if you want to return a value early from the function (before the last line), you’ll want to use return.

Here is a simple example of a function that returns a value early. Interestingly, the code compiles! It even returns the same Hello, world number 8 output as before:

fn give_number() -> i32 {

return 8;

10;

}

fn main() {

println!("Hello, world number {}", give_number());

}

It compiles because there is nothing wrong with the code: the give_number() function returns an i32 as it is supposed to. However, Rust does notice that the function will never reach the line below return 8; and gives a warning:

warning: unreachable expression --> src/main.rs:3:5 | 2 | return 8; | -------- any code following this expression is unreachable 3 | 10; | ^^ unreachable statement | = note: `#[warn(unreachable_code)]` on by default

When you want to give variables to a function, put them inside the (). You have to give them a name and write the type:

fn multiply(number_one: i32, number_two: i32) { #1

let result = number_one * number_two;

println!("{} times {} is {}", number_one, number_two, result);

}

fn main() {

multiply(8, 9); #2

let some_number = 10; #3

let some_other_number = 2;

multiply(some_number, some_other_number); #4

}

8 times 9 is 72 10 times 2 is 20

fn multiply(number_one: i32, number_two: i32) -> i32 {

let result = number_one * number_two; #1

result #2

}

fn main() {

let multiply_result = multiply(8, 9);

println!("The two numbers multiplied are: {multiply_result}");

}

The two numbers multiplied are: 72

In fact, we don’t even need to declare a variable before returning it. This code generates the same output:

fn multiply(number_one: i32, number_two: i32) -> i32 {

number_one * number_two #1

}

fn main() {

let multiply_result = multiply(8, 9);

println!("The two numbers multiplied are: {}", multiply_result);

}

One reason that Rust is so fast is that it knows exactly how long variables need to use memory. Once the variables don’t need memory, they are dropped, and Rust frees up that memory automatically. Let’s now learn about declaring variables and how long they live for.

NOTE

How Rust manages memory is different from garbage collection! Most languages have a garbage collector that handles cleaning up memory. In other languages like C and C++, you clean up memory yourself. Rust doesn’t have a garbage collector, same as C and C++. But Rust is also different: it is smart enough to know exactly when a variable doesn’t need to exist anymore and frees the memory for you.

highlight, annotate, and bookmark

You can automatically highlight by performing the text selection while keeping the alt/ key pressed.

In Rust, we use the let keyword to declare a variable. A variable is just a name that represents some type of information in the same way that a real name represents a person:

fn main() {

let my_number = 8; #1

println!("Hello, number {}", my_number);

}

fn main() {

let my_number = 8;

println!("Hello, number {my_number}");

}

In this book, we’ll use both methods for printing. Sometimes writing the variable name inside {} looks better:

fn main() {

let color1 = "red";

let color2 = "blue";

let color3 = "green";

println!("I like {color1} and {color2} and {color3}");

}

fn main() {

let naver_base_url = "naver";

let google_base_url = "google";

let microsoft_base_url = "microsoft";

println!("The url is www.{naver_base_url}.com"); #1

println!("The url is www.{google_base_url}.com"); #1

println!("The url is www.{microsoft_base_url}.com"); #1

println!("The url is www.{}.com", naver_base_url); #2

println!("The url is www.{}.com", google_base_url); #2

println!("The url is www.{}.com", microsoft_base_url); #2

}

As we saw previously, a variable’s lifetime starts and ends inside a code block: {}. This example will generate an error because my_number is inside its own code block and its lifetime ends before we try to print it:

fn main() {

{

let my_number = 8; #1

}

println!("Hello, number {}", my_number); #2

}

However, you can return a value from a code block to keep it alive. Take a close look at how this works:

fn main() {

let my_number = {

let second_number = 8;

second_number + 9 #1

};

println!("My number is: {}", my_number);

}

The value of second_number is 8, and we return second_number + 9, so this is like writing let my_number = 8 + 9. And because the block returns the value, my_number never lives inside the block; instead, it gets its value from the return value at the end of the block.

fn main() {

let my_number = {

let second_number = 8; #1

second_number + 9; #2

};

println!("My number is: {:?}", my_number); #3

}

discuss

Simple variables in Rust can be printed with {} inside println!. This is called Display printing. But some variables won’t be able to use {} to print, and you need Debug printing. You can think of Debug printing as printing for the programmer because it usually shows more information—and is usually less pretty.

How do you know if you need {:?} and not {}? The compiler will tell you. Let’s try printing () with Display to see the error:

fn main() {

let doesnt_print = ();

println!("This will not print: {}", doesnt_print);

}

error[E0277]: `()` doesn't implement `std::fmt::Display` --> src\main.rs:3:41 | 3 | println!("This will not print: {}", doesnt_print); | ^^^^^^^^^^^^ `()` cannot be formatted with the default formatter | = help: the trait `std::fmt::Display` is not implemented for `()` = note: in format strings you may be able to use `{:?}` (or {:#?} for pretty-print) instead = note: required by `std::fmt::Display::fmt`

This is quite a bit of information. There is also one important word here: trait. Traits are important in Rust, and we will learn about them throughout the book. But for now, you can think of the word trait as “what a type can do.” So if the compiler says The trait Display is not implemented, it means “the type doesn’t have Display capabilities.”

you may be able to use {:?} (or {:#?} for pretty-print) instead.

This means that you can try {:?} or {:#?}. {:#?}, is known as “pretty printing.” It is the same as Debug with {:?} but prints with different formatting over more lines.

User { name: "Mr. User", user_number: 101 }

User {

name: "Mr. User",

user_number: 101,

}

fn main() {

print!("This will not print a new line");

println!(" so this will be on the same line");

}

- {}—Display print. More types have Debug than Display, so if a type you want to print can’t print with Display, you can try Debug.

- {:?}—Debug print. If there is too much information on one line, you can try {:#?}.

- {:#?}—Debug print, but pretty. Pretty means that each part of a type is printed on its own line to make it easier to read.

There is quite a bit more to printing in Rust, and we will learn more about it in the next chapter. Now, let’s get back to some more basic information about Rust’s easiest types.

settings

If you want to see the smallest and biggest numbers, you can use MIN and MAX after the name of the type:

fn main() {

println!("The smallest i8: {} The biggest i8: {}", i8::MIN, i8::MAX);

println!("The smallest u8: {} The biggest u8: {}", u8::MIN, u8::MAX);

println!("The smallest i16: {} The biggest i16: {}", i16::MIN, i16::MAX);

println!("The smallest u16: {} and the biggest u16: {}", u16::MIN, u16::MAX);

println!("The smallest i32: {} The biggest i32: {}", i32::MIN, i32::MAX);

println!("The smallest u32: {} The biggest u32: {}", u32::MIN, u32::MAX);

println!("The smallest i64: {} The biggest i64: {}", i64::MIN, i64::MAX);

println!("The smallest u64: {} The biggest u64: {}", u64::MIN, u64::MAX);

println!("The smallest i128: {} The biggest i128: {}", i128::MIN, i128::MAX);

println!("The smallest u128: {} The biggest u128: {}", u128::MIN, u128::MAX);

}

The smallest i8: -128 The biggest i8: 127 The smallest u8: 0 The biggest u8: 255 The smallest i16: -32768 The biggest i16: 32767 The smallest u16: 0 and the biggest u16: 65535 The smallest i32: -2147483648 The biggest i32: 2147483647 The smallest u32: 0 The biggest u32: 4294967295 The smallest i64: -9223372036854775808 The biggest i64: 9223372036854775807 The smallest u64: 0 The biggest u64: 18446744073709551615 The smallest i128: -170141183460469231731687303715884105728 The biggest i128: 170141183460469231731687303715884105727 The smallest u128: 0 The biggest u128: 340282366920938463463374607431768211455

By the way, MIN and MAX are written in all capitals because they are consts (unchangeable global values). In this case, they are consts, which are attached to their types with a :: in between. We will learn more about consts in the next chapter.

highlight, annotate, and bookmark

You can automatically highlight by performing the text selection while keeping the alt/ key pressed.

fn main() {

let my_number = 8;

my_number = 10;

}

You can’t change my_number because variables are immutable if you only write let. The compiler message is pretty detailed:

error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable `my_number` --> src/main.rs:3:5 | 2 | let my_number = 8; | --------- | | | first assignment to `my_number` | help: consider making this binding mutable: `mut my_number` 3 | my_number = 10;

But sometimes you want to be able to change your variable, and the compiler has given us some advice if we want to do so. To make a variable that you can change, add mut after let:

fn main() {

let mut my_number = 8;

my_number = 10;

}

Now there is no problem. However, you cannot change the type of a variable even if you declare it as mut. So the following will not work:

fn main() {

let mut my_variable = 8;

my_variable = "Hello, world!";

}

error[E0308]: mismatched types --> src/main.rs:3:19 | 2 | let mut my_variable = 8; | - expected due to this value 3 | my_variable = "Hello, world!"; | ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^ expected integer, found `&str`

discuss

Take our tour and find out more about liveBook's features:

- Search - full text search of all our books

- Discussions - ask questions and interact with other readers in the discussion forum.

- Highlight, annotate, or bookmark.

Now that we know the basics of mutability, it’s time to learn about shadowing. Shadowing means using let to declare a new variable with the same name as another variable. It looks like mutability, but it is completely different. Be sure not to confuse them! Shadowing looks like this:

fn main() {

let my_number = 8; #1

println!("{}", my_number);

let my_number = 9.2; #2

println!("{}", my_number);

}

Here we say that we “shadowed” my_number with a new “let binding.” The variable my_number is now pointing to a completely different value.

So, is the first my_number destroyed? No, but when we call my_number, we now get my_number the f64. Because they are in the same scope block (the same {}), we can’t see the first my_number anymore.

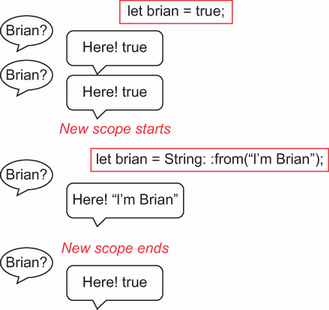

But if they are in different blocks, we can see both. Let’s take the same example and put the second my_number inside a different block to see what happens:

fn main() {

let my_number = 8;

println!("{}", my_number);

{

let my_number = 9.2;

println!("{}", my_number); #1

}

println!("{}", my_number); #2

}

So, when you shadow a variable with a new variable with the same name, you don’t destroy the first one. You block it.

Imagine that there’s a classroom with a student named Brian who always says true (he’s a bool). Every time you call out his name, he tells you his value. Then one day a new student comes in who is also named Brian and sits in front of the other Brian. The second Brian is shadowing the first one.

This second Brian is a completely different type: he’s a string that says “I’m Brian” every time. Now, every time you call Brian and ask his value, you’ll get something completely different. But let’s say that the second Brian was only visiting from another school and later leaves—he’s in a smaller “scope.” Now, when you call out the name Brian, you’ll hear true again because the first Brian is still there (his scope lasts longer).

What is the advantage of shadowing? Shadowing is good when you need to work on a variable a lot and you don’t care about it in between. Imagine that you want to do a lot of simple math with a variable:

fn times_two(number: i32) -> i32 {

number * 2

}

fn main() {

let final_number = {

let y = 10;

let x = 9;

let x = times_two(x); #1

let x = x + y; #2

x #3

};

println!("The number is now: {}", final_number)

}

Without shadowing, you would have to think of different names, even though you don’t care about x. Let’s pretend we wanted to do the same thing, but Rust didn’t allow shadowing. We would have to come up with a new variable name each time:

fn times_two(number: i32) -> i32 {

number * 2

}

fn main() {

let final_number = {

let y = 10;

let x = 9;

let x_twice = times_two(x); #1

let x_twice_and_y = x_twice + y; #2

x_twice_and_y

};

println!("The number is now: {}", final_number)

}

Shadowing can be useful when working with mutability, too. In the following example, we have a number called x again. We’d like to change its value, and we don’t care about the original variable called x. In this case, we can shadow it with a new mutable variable that is a float, and now we can change it:

fn main() {

let x = 9

let mut x = x as f32;

x += 0.5; #1

}

In general, you see shadowing in Rust in cases like these: working quickly with variables we don’t care too much about or getting around Rust’s strict rules about types, mutability, and so on.

So that’s it for the first chapter. If you know another programming language, you might have noticed that Rust is very familiar but quite different in some areas. And if Rust is your first language, that’s fine, too. Everything will be new to you, but you won’t have any habits to unlearn either.

In the next chapter, we are going to learn about how memory works and how data is owned. Ownership is one of Rust’s most unique concepts, so we’ll spend a lot of time thinking about it.

- You can write whatever you want in your comments, and if you write them with ///, Rust can automatically use them to document your code.

- You can tell Rust the type name of a variable you are making, but most of the time, you don’t need to.

- Understanding how binary works gives you a sense of which integer type is best to use.

- Variables live inside {} code blocks (scopes). Variables created inside can’t leave them unless they are the return value into another larger scope.

- You can change a variable in Rust if you make it mutable with mut. Otherwise, the compiler will give an error if you try.

- Shadowing is completely different from mutability: it’s just a variable with the same name that blocks the other one.